Products You May Like

At age 15, Yulin Kuang made a deal with herself: If she could get on a fanfiction site’s end-of-year top-10 list with one of her Harry Potter romances, she would go on to have a career as a professional writer.

“I did make that list,” she informs me, years later, over Zoom. “So I was like, Sweet.” Mission accomplished.

And while the fanfiction-writer-to-traditionally-published-author pipeline is by now well-trodden, Kuang’s transition from Lily/James short stories (a.k.a. one-shots) to her numerous projects today—among them two film adaptations of romance phenomenon Emily Henry’s books, and a debut novel of her own—wasn’t quite so direct. She attended Carnegie Mellon for creative writing, as well as international relations and politics, from which she intended to join the White House Press Corps, only to realize working in Washington didn’t bear much resemblance to The West Wing or Gilmore Girls. (Kuang’s a “millennial to my core,” she admits.) “I was writing all these things about, ‘What do you think is stopping us from world peace?’” she says. “And I was just like, ‘I don’t know!’”

So she started writing screenplays between classes, and handed them off to other students to direct. She was rarely impressed with the final product: “My scripts weren’t very good, but, also, I felt like everybody was fucking it up. So I was like, ‘I will do it.’” She stayed on campus over spring break one year to direct her own short film, during which she met the man who’d become her husband, and discovered a sincere love for directing. After graduation, she made the leap to Los Angeles and sent her projects to film festivals while working in talent relations as part of the NBCUniversal Page Program. But as a rom-com devotee—she named her car after Nora Ephron—with a particular penchant for coming-of-age stories, the film festival demographics were rarely suitable. “Especially at the Palm Springs Film Festival, the median age is about 65, and the title of [my short film] was The Perils of Growing Up Flat-Chested,” Kuang says. “Somebody told me, ‘You should check out VidCon, which is this convention for online video.’ And so I go there to the Anaheim Convention Center, and it was a sea of screaming teenage girls. It was like, ‘My people.’”

Inspired, Kuang launched two YouTube channels and began piecing together transmedia stories in which fans could contribute fan art and fanfiction, which—if Kuang reblogged them to Tumblr—would become part of the story canon. The project “went Tumblr viral, which is not the same as regular viral,” Kuang specifies, but it was enough to catch the attention of a production company, which ultimately jump-started Kuang’s Hollywood career. Fast-forward many pitches and spec scripts, many projects launched and abandoned, others stuck in infamous development hell (including an adaptation of fellow romance author Maureen Goo’s I Believe In A Thing Called Love), and Henry’s People We Meet on Vacation manuscript finally landed on Kuang’s desk.

“I remember reading it and just being like, ‘There’s more locations than a James Bond movie in here,’” Kuang says. “But it is doing what I want to do in terms of romance and reinvigorating the genre. I think rom-coms can have this flattened feeling, sometimes, because we associate comedy with it so much. But I think there are things on the bluer side of the human emotional spectrum within Emily’s work that I really resonate with.”

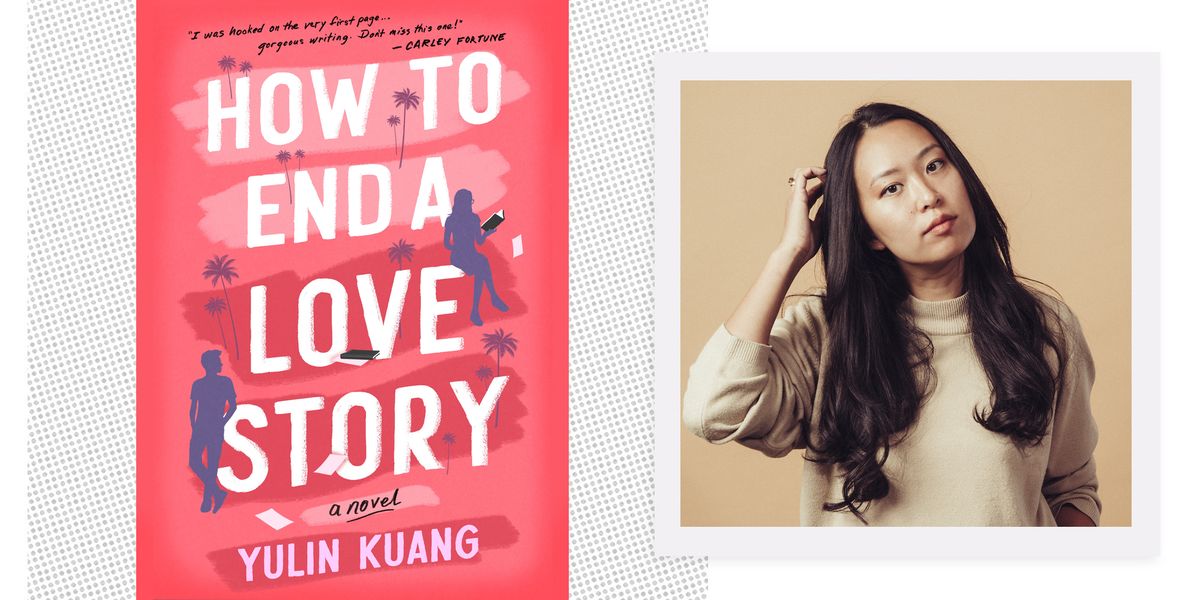

Now, Kuang is adapting People We Meet on Vacation as well as adapting and directing another of Henry’s novels, Beach Read. With so much adaptation consuming her hours, Kuang yearned to carve out space for something of her own. The result of that creative soul-searching is a contemporary enemies-to-lovers romance novel, How to End a Love Story, out April 9 from Avon, about a screenwriter and a novelist linked through a childhood tragedy. When, years later, they’re hired to work together on a television adaptation of the novelist’s bestselling YA books, the duo must confront both their undeniable attraction and the pain of a suicide that still shapes how they see each other.

Ahead, Kuang discusses her path to How to End a Love Story—a steamy, hilarious, bittersweet tale—and her adventures bringing Henry to Hollywood.

What made you decide, in the midst of such an already-packed schedule, that you wanted to write a book?

Yeah, I didn’t set out to write a book. I was going to write myself a feature. And then I was sitting there thinking about how, well, If I write a feature, I’m going to have to think about what production budget could I realistically get? What producers could I get? What actors would agree to do this? And then where am I going to sell it? And then if I sell it, will the people who buy it eventually leave the company, and then will this orphan project die again?

So then I was scrolling through Instagram and I think I saw Sarah MacLean, one of my favorite historical romance authors, advertising a “Start Your Romance Novel” writing workshop Zoom. And I was like, I should do that. I enjoyed prose back in my fanfic-writing days, and I missed a beautiful sentence. We have no use for beautiful sentences in a screenplay because there’s got to be a real economy of language there. So I was like, This could be fun.

It was the pandemic, and I feel like the pandemic made us all think about, If tomorrow is not promised, then what do I want to do with my time? I wanted to write something where, once I was done with it, that was the finished object. And also, if it’s bad, I’ll just never show anybody.

What about the idea itself? The main characters, Helen and Grant, share characteristics of your own life in that one’s a novelist and the other a screenwriter, but they share this tormented history.

I knew going into writing the novel that I wanted it to be something that would require zero research because I was really busy. I wanted it to be a screenwriter and a novelist who had known each other in high school, and that they were in the writers’ room for an adaptation.

The conceit of it [that these two characters would be united by a suicide] came to me very late. I wanted to explore what a shared wound would do to two different people who were coming at it from different angles. I have known a couple of people over the years—some are friends, and some are more acquaintances—who have lost a sibling to suicide. I have a friend who is a fellow YouTuber, Anna Akana. She lost her sister to suicide, and she has been very vocal about it on YouTube and also in her most recent standup special, which I loved. When I came up with the idea, I did actually think of Anna, and I was like, “Oh, will this be weird? Should I text her and ask her if it’s okay for me to write this story?” And then I was like, I might not even finish it, so I’m just going to write it and then see. She ended up being my sensitivity reader for the project, which was really great.

What parts of yourself did you plug into Helen and Grant?

I kind of bisected myself, I think. Helen was this alternate timeline version of me. I studied creative writing in undergrad. And I did, at one point, think I was going to go into publishing. But I just didn’t end up going that route.

I thought of [Helen] as, What if I had ended up in New York instead of L.A. at the end of all of this? And then Grant was kind of me more established—but also not me, more like people I have coveted or people with skills I have coveted over the years. His defining trait, I would say, was that he was “good in a room,” which was the original title [of How to End a Love Story]. I’ve always been compelled by people who are charming publicly, and then when you get to know them in private, they’re the most insecure people. I thought that was interesting to explore.

When did the title switch from Good in a Room to How to End a Love Story?

Well, the title switch happened because we were trying to come up with a cover, and I didn’t want [drawings of] people on my cover. So I realized I had to do something to the title to indicate it was a romance. I had this word-salad Notes app document that was like, “Love This,” “Love That,” “Love the Right Way,” blah, blah, blah. I remember reading them all out to my agent, and during the call she was like, “That one’s a title.” So then we came up with that title; it went on the cover. We had a beautiful cover, and then the sales department said, “Nobody will know what this book is about, actually.” And so we changed the cover, and it does have people on it now.

They’re subtle.

Yeah, they’re subtle people. I think my instinct is always like, “I want to do something different!” But I think that that is why I don’t work in sales because I’m chasing my own taste, and I feel like there’s this the Elphaba-Glinda tension of, “Just let me make you popular!”

Would you want to adapt a film version of this book?

Not a film version, but I would do TV in a heartbeat.

Adaptation is ubiquitous. Literary IP seems to be more in-demand than ever before, and you make a few meta jokes about it in How to End a Love Story. As someone on both sides of the business now, how do you feel about the modern book-to-Hollywood landscape?

One of my primary motivators for getting into Hollywood was watching the announcements for the Harry Potter movies. I am part of the generation that got to grow up with the books. So when I watched the announcements happening, I was just like, God, I hope they don’t fuck up my literal childhood. I felt it so, so deeply that I dreamed and schemed and told myself, one day, I will have influence over the books and the adaptations of the books that I care about. So I definitely got here on purpose. I’ve won a lot of lotteries of birth, but I also tried very hard to get to this point.

That being said, once I did get here, I think I understood a lot more. I had some very early meetings on books I wanted to adapt that I didn’t get, because I would go into that meeting and I would be like, “We’ll just make it exactly like the book!” And then they would be like, “Okay, cool, bye.”

I realized [adaptations] do need a point of view. So that was when my fanfiction background came in handy. Then, once I did get the jobs—there’s no way for me to put every single line of this 380-whatever-page book into the script. So finding visually compelling ways to convey the interiority of books was my focus.

But I also understand adaptation fatigue. As much as I love adaptation, I also think that there is such value in creating something original. Cinema is one of the newest art forms we have. So a lot of the early stuff was adaptation, and it makes sense to me that [film] will always have this kind of marriage with adaptation. But I think I want to see things that are organically created for the medium itself. There will always be room for adaptation, but I would love to see Hollywood take more risks on original work.

By now, you’re immersed in Emily Henry’s world. You’re working on two really high-profile profile films. The two of you now write books in the same market. That’s a fascinating relationship between an author and adapter. What has that been like for you?

I was talking to Emily yesterday about this. It feels like we were put in a marriage of convenience by our respective industries, because I did not get the chance to discover Emily’s work organically. It was always sent to me fairly early on. I obviously resonated with it. In the beginning, she kind of loomed large in my head because it was like, I don’t know you. But I know so much about how I respond to your work. So it was this interesting thing where, maybe, we were both a little wary of each other.

I do think there is a tension between novelists and their adapters. Now that I’ve written a book, I’m like, yeah, I would be inherently so suspicious of that person. “Are you in this for the right reasons? Is this a paycheck for you?” On my end, it was also this feeling of, “I don’t want to disappoint your readership, but I also want to feel free to take this into a different medium and see what we can do there.” That tension wasn’t ever from anything Emily said or did; it was more my own feeling and memories of caring so much about the adaptations of my favorite books.

We started talking a lot more as we got more into the revision process, and that’s been fun to watch our dynamic unfold. I think we’ve got this black-cat, golden-retriever vibe going, and I think that’s fun. Emily and I are both drawn to ’90s rom-coms and art with heart and a meta component. It’s been really fun to dive into the mind of somebody I really respect and figure all that.

What stage are you at with both People We Meet on Vacation and Beach Read?

I am revising both. There’s a studio draft that was turned in and I got notes on that one. And then the other one, I just got hired to do a rewrite on that one as well. So they’re both still awaiting a green light.

There’s a lot of speculation about these movies. I’m sure you saw the absolute fervor that you and Emily ignited when you both reposted photos of Paul [Mescal] and Ayo [Edebiri] on your Instagram Stories. What is it like for you to have that much attention and excitement on a project like this? Can you ever drown it out?

I guess my way to answer this is… One of my favorite story structure templates is Dan Harmon’s Story Circle, and it’s what I use to break every TV pilot. It goes: A character starts in their normal world, but they want something and then they leave, and then they get the thing that they want, but it costs a heavy price. And then they return to their normal world having changed. And I would say I came from the world of fandom. I desperately wanted this [job] that I have now. The thing that it has cost me is, I don’t think that I can be in fandom spaces the way that I once was. Because there is a boundary that needs to exist. So I cannot look or engage with that as directly as I used to in order for me to protect my own mental health and also the adaptations that I’m working on. Because if I pay too much attention to what people are saying, that will drive me to slow madness.

For a while I was feeling very disconnected from my creative roots because fandom had always been such a large part of my background. There is such a fandom for these things that I’m working on, but also, I don’t feel like it is wise for me to engage with it directly at this point. I’m like, Oh, you guys are saying funny things online, and I want to make shit posts. But I think that if I make shit posts, that might be newsworthy.

Having come from fandom spaces myself, I can imagine how there must be a strange sort of mourning there when you can’t engage in that community in the same way.

Yeah. To be clear, nobody should feel sorry for me because I am living my dream. I will happily take this mourning feeling and stay on this side. But yes, know that I miss it. Know that I remember. I remember everything.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.