Products You May Like

Rachel Brem, MD, already had a plan. She was going to get a prophylactic mastectomy, determined to get ahead of breast cancer this time. When Dr. Brem was just 12, her mother had been diagnosed and told she had six months to live. Though her mom ultimately underwent a successful surgery and lived another 44 years, the experience left a lasting impact. “Our lives were completely turned upside down,” Dr. Brem recalls. It’s what propelled Dr. Brem into medicine in the first place and convinced her of the importance of early detection; part of why her mother was able to beat breast cancer was because it had been caught early.

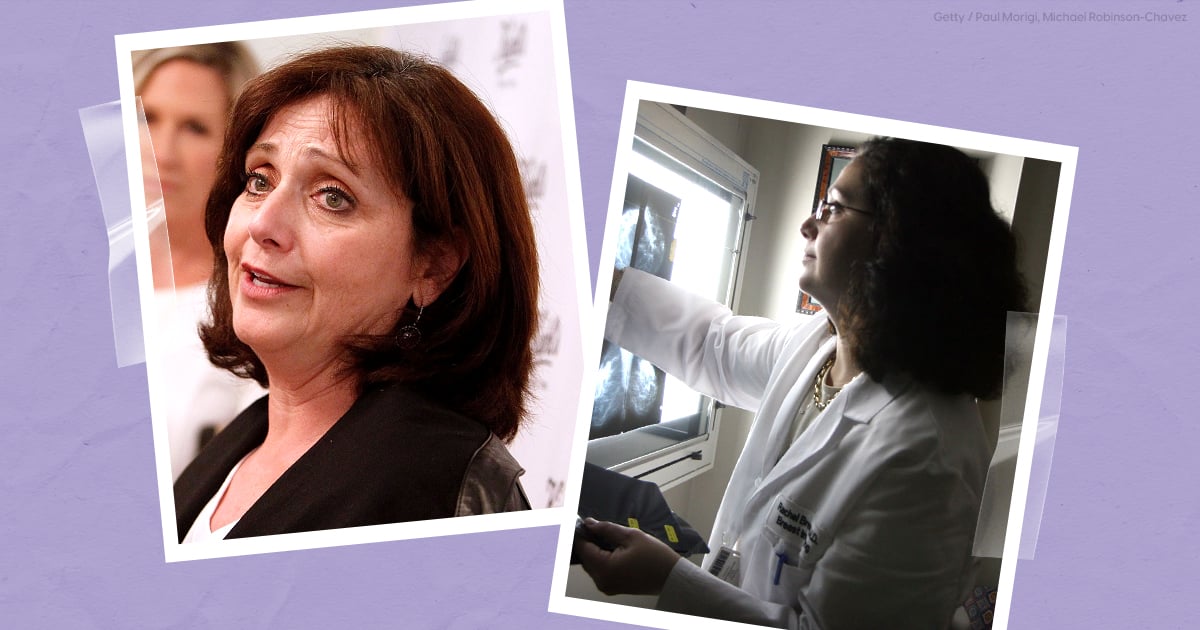

Dr. Brem didn’t want her own children to go through what she had, so she got tested for the BRCA gene. When the results came back positive, she decided to have a bilateral preventative mastectomy. At the time, Dr. Brem felt more prepared than most to make such a huge decision. She was an MD, working as the director of breast imaging at Johns Hopkins.

“You can try to trick [breast cancer], but you can never really be sure that you’re gonna get away with it.”

But, of course, cancer doesn’t care about education, experience, or how well someone may understand the disease, and it doesn’t adhere to timelines. “You can try to trick [breast cancer], but you can never really be sure that you’re gonna get away with it,” Dr. Brem says.

At 37 years old, she learned that the hard way.

Months before her preventative mastectomy, Dr. Brem was testing out ultrasound equipment for different vendors — something she did regularly as part of her job. “After a day of seeing patients, I would try the equipment on on myself, and see which one has the best image quality. And so, that evening, I found out which one has the best image quality, but as I was scanning myself, I also found my own breast cancer.”

The discovery came with a flood of emotions. On the one hand, Dr. Brem felt “lucky about the power of knowledge.” But she was also simply terrified. “I had three young daughters. I didn’t know that I was going to survive to raise them,” she tells PS. On top of that: “The idea of cancer surgery — which is much more intense than the kind of surgery that I planned to have — and going through chemotherapy, it’s terrifying for anybody,” Dr. Brem says.

Fortunately, breaking the news to her children wasn’t as traumatic as her own experience growing up. “My daughters had been had been living with the idea of breast cancer all their life — that’s what their mother did [for work],” she tells PS. “That was dinner talk.” In many ways, Dr. Brem feels lucky for that. Despite not breaking the generational diagnosis, she was able to break the trauma.

Cancer treatment is never easy, but Dr. Brem knows enough about what the journey can look like to appreciate that her experience was relatively seamless. She also knows that often isn’t the case. “When a woman is diagnosed with breast cancer, if it’s medically reasonable, they say, ‘Do you want to a lumpectomy or a mastectomy?’ And the answer is, ‘Gee, I really don’t want breast cancer,'” she says. “You have to make these crazy profound, life-altering decisions with so little information.” Dr. Brem couldn’t imagine having to do so without the years of medical training under her belt.

Not to mention, breast cancer is not an equal-opportunity disease, Dr. Brem point outs. Ashkenazi Jewish women are 10 times more likely to have the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation than the general US population. And Black women die of breast cancer at a much higher rate because they get this more aggressive form of triple negative breast cancer. Couple that with lack of access, socioeconomic barriers, racial disparities in healthcare and the odds of survival can become discouraging. Investing in early detection efforts are crucial, Dr. Brem tells PS.

That why she not only co-authored a book, “No Longer Radical,” about navigating mastectomies — but also founded the Brem Foundation, an organization dedicated to making early detection possible for more people via access, education, advocacy. Since it’s inception, the foundation has launched partnerships like Wheels For Women with Lyft — which provides free rides tomammogram appointments for low-income women — and CheckMate, an online quiz, designed to interpret your risk factors and suggest what you should talk to your doctor about in regards to breast cancer. And personally, as the director of the breast imaging and intervention center at the George Washington Cancer Center, she has made it her mission to invest in and work toward developing new technologies for the early detection of breast cancer.

The through-line of it all: early detection. It’s been an essential part of Dr. Brem’s work and decades-long career. It’s what she credits to saving her own life and that of her mom’s. And it’s what she believes will carry us into the future.

“We kind of do have a cure for breast cancer — [it’s] early detection,” Dr. Brem says. In focusing efforts there, she hopes that for an increasing number of women, breast cancer can be like any other chronic disease, like hypertension or diabetes. “That people can live with breast cancer, even metastatic breast cancer for decades,” she says.

Alexis Jones is the senior health editor at POPSUGAR. Her areas of expertise include women’s health, mental health, racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare, diversity in wellness, and chronic conditions. Prior to joining POPSUGAR, she was the senior editor at Health magazine. Her other bylines can be found at Women’s Health, Prevention, Marie Claire, and more.

Image Source: Getty / Paul Morigi Michael Robinson-Chavez