Products You May Like

Black women and girls are regularly erased from public memory. When they are killed at the hands of police, the obscurity and omission deepen. This erasure takes many forms: Lack of media coverage. Exclusion from public memorials. Failure to teach their stories in schools.

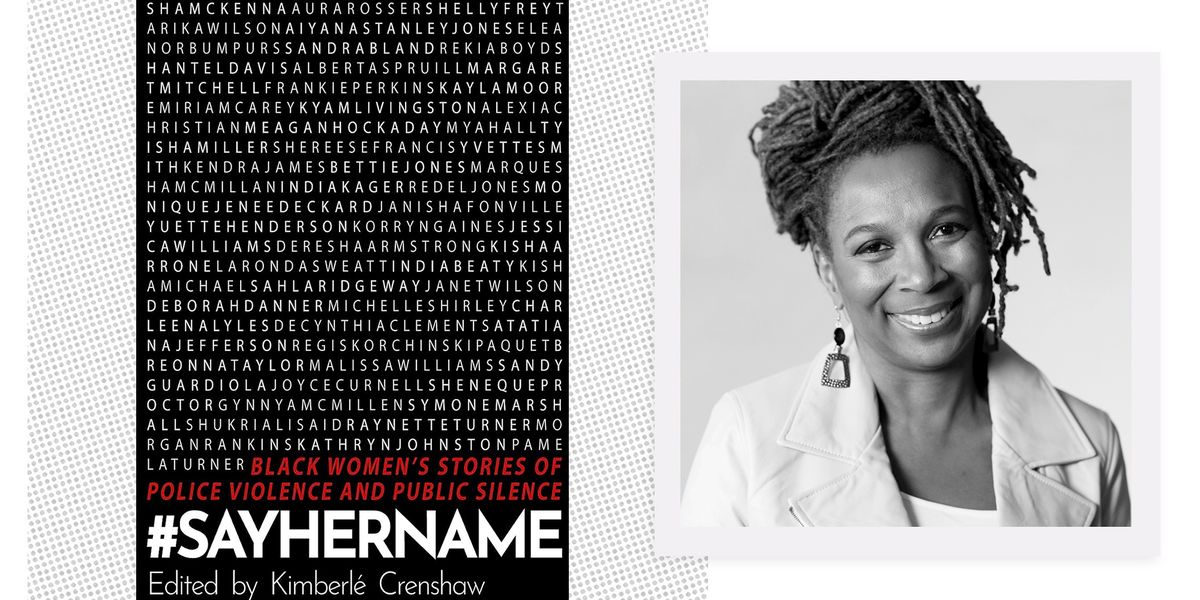

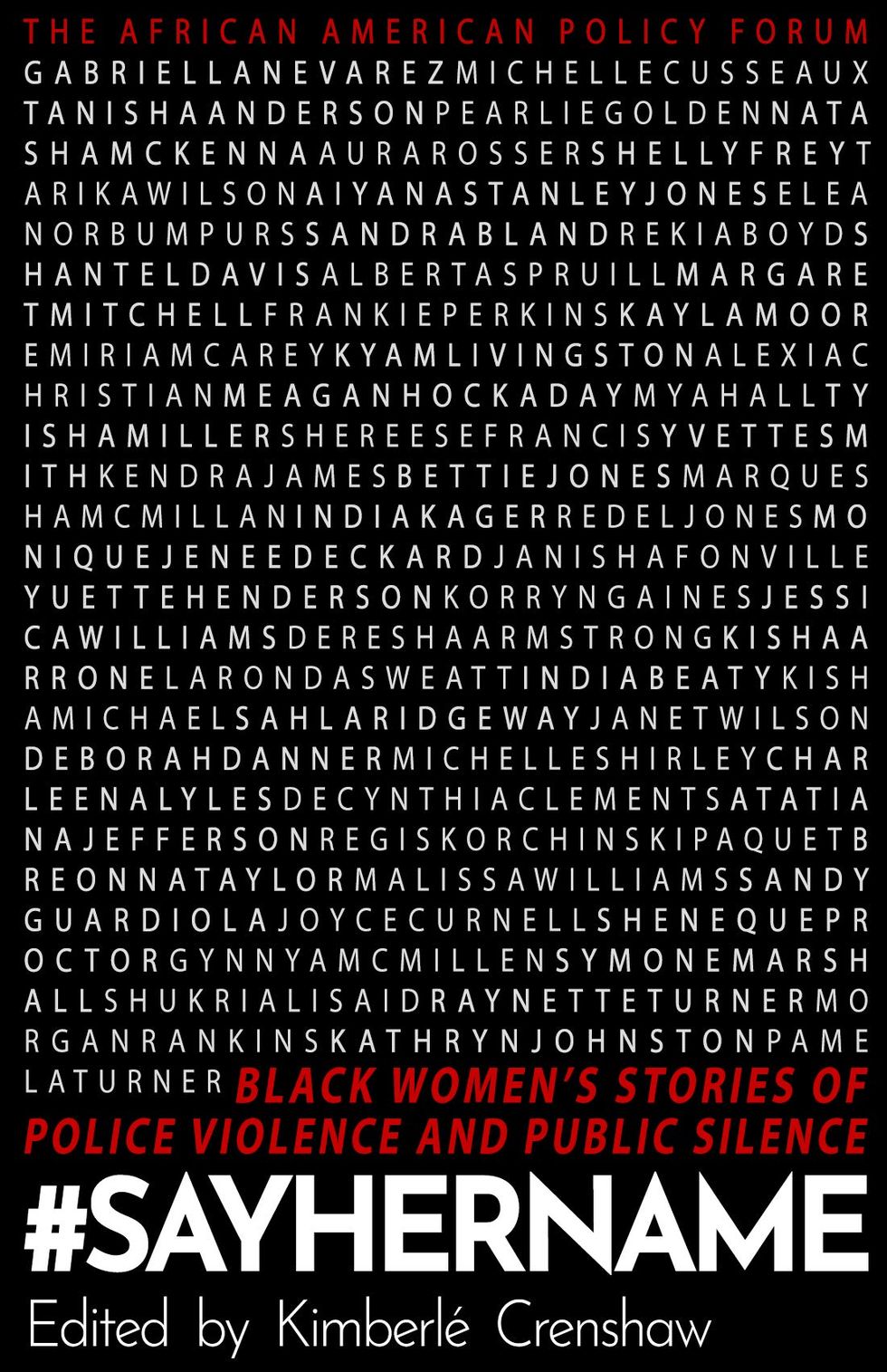

In Kimberlé Crenshaw’s new book #SayHerName: Black Women’s Stories of State Violence and Public Silence, out today, the UCLA and Columbia University law professor thoughtfully memorializes 177 Black women killed between 1975 and 2022, zeroing in on nine narratives told by their loved ones who make their grief known through vivid storytelling. Throughout the haunting book she co-authored with her social justice think tank, the African American Policy Forum, she interweaves meticulous research and emphatic, stinging commentary to paint a poignant and often distressing picture of the state of racialized gender violence.

“If we can’t hold Black women who’ve been killed by police with the same care and concern as we hold our brothers and our sons,” Crenshaw tells me, “if we can’t do it for them, then we can’t do it for any set of issues in which Black women are marginalized and challenged.”

Crenshaw is renowned for her work. A dedicated and ardent activist with a wealth of knowledge, she’s been the eminent voice in the fight against intersectional violence, with a distinguished background in civil rights, Black feminist legal theory, race, racism, and the law; she also coined the terms “Intersectionality” and “Critical Race Theory.” As we chatted Saturday, ever warm and self-effacing, she tells me working on the book was “an emotional challenge” but a necessary one because such losses happen when people cannot see the problem or struggle to understand it. As someone who’s studied her work, it doesn’t take long for us to get absorbed in the invisibility crisis plaguing Black women, how it’s a pervasive epidemic that’s overlooked and ignored. We continue on about how in #SayHerName, Crenshaw wants people to grasp the consequences of what she calls the secondary loss: the erasure of what has happened to the families who suffer in silence.

The book is titled after the popular hashtag for the social movement Crenshaw created alongside AAPF in December 2014. It began as an organizing effort to end state-sponsored violence informed by racial and gender biases in response to the compounding and nationally-recognized gut-wrenching deaths of Black men and boys. Specifically following the deaths of Eric Garner (July 17, 2014), Michael Brown (August 9, 2014), and Tamir Rice (November 22, 2014), where Black women and girls who were being killed in the same way around the same time were being banished into infinite invisibility. For example, Tanisha Anderson was killed on November 13, 2014, by the same Cleveland Police Department that killed Rice, yet received little media coverage and community galvanization. “It’s one thing to lose your daughter to police violence,” Crenshaw once told me, “that’s unimaginable. But it’s another thing when the communities don’t take up your daughter’s case.”

A more recent fatal encounter comes to mind. Breonna Taylor’s March 2020 death at the hands of the Louisville Police Department received little media attention, too, until George Floyd’s slaying brought the nation to a halt on May 25, 2020. It’s this kind of negligence over the bodies of Black women that the book and the movement it’s named after aim to magnify. They call for a gender-inclusive approach to racial justice that centers all Black lives equally.

#SayHerName also points to prominent crusades, like Black Lives Matter, for tending to focus on male-centric thinking. “A persistent problem in anti-racist organizing,” Crenshaw writes, “is the internalization of narratives about anti-Black racism that are inflected with harmful assumptions about gender. At the root of this problem is the degree to which some stories—those principally involving male victimization—are treated as representative of the whole; while other stories involving non-male gendered vulnerabilities become imbued with particulars that render them ‘not really’ or ‘not only’ about race.”

And while movements like BLM and its catchphrase appear inclusive on its face—in that it doesn’t call out any gender or sexual orientation—most of the cases it propelled, mainly using its hashtag, have been men. One study found that in the year following Brown’s death, of all the hashtags used to condemn police violence, none were for a Black woman or girl.

The book also goes in on some alarming statistics. It unveils the cyclical nature of Black women and girls being systematically disregarded. It outlines how Black women are the only race-gender group to have most of its members killed while unarmed: “From May 1, 2013, to January 1, 2015, 57 percent of Black women were unarmed when killed.” It also makes the point that media outlets play a significant role in the invisibility crisis. Black women make up about 10 percent of the female population in America but account for one-fifth of all women killed by police. Yet, news outlets have been found to mention male victims of police brutality more often than female victims of police.

This gender discrepancy is why #SayHerName has become a commanding characterization of how racism and sexism materialize on Black women’s bodies. It’s a critical corrective that’s become synonymous with amplifying the names and narratives of Black women, girls, and femmes killed by police and rendered invisible by society.

As Crenshaw sees it, Black women and girls continue to be made invisible because there is an absence of frameworks that allow people to understand the different ways racism is experienced across gender, age, and class. “That’s what intersectionality helps people see,” she says. “We understand anti-Black racism, but do we understand how it plays out when the police are called when a Black woman is having a mental health crisis? How their reaction to her is gonna be different than their reaction to a white woman? That’s what intersectionality adds to our understanding that Black bodies are always seen and treated differently than white bodies.” Then, it becomes a matter of excavating how gender contributes to that difference. When there’s anti-racism without an explicit “anti-patriarchal understanding of it,” the experiences of Black women and girls are further erased.

What’s most glaring and intentional about Crenshaw and AAPF’s approach to this heartbreaking, necessary and significant contribution to history is the spotlighting of the many unsung names most of us have never heard: Denise Hawkins (killed November 11, 1975). Netta Africa (May 13, 1985). LaTanya Haggerty (June 4, 1999). Tiraneka Jenkins (July 14, 2009). April Webster (December 16, 2018).

#SayHerName makes the gripping case that there is an institutionally shaped indifference toward Black women’s experiences. It is a vicious cycle that has led society to believe that Black women and girls are not at risk—one that has magnified a common perception that Black women are disposable. We’ve become invisible. Our contributions dismissed or minimized. Our stories distorted or excluded from historical narratives. Our voices silenced, time and again. There is a never-ending neglect to understand why society continues to punish and forget Black women and girls, all rooted in patriarchy, misogyny, and white supremacy. It is a system that has penalized the same people it has ignored since the very beginning, allowing for no gaps to be bridged. Black women have become one of the most unmistakable embodiments of cyclical victimization.

In the book, Crenshaw connects the dots for us. To effectively fight against racist police violence, we must recognize and embrace the gendered dimensions of our history. To do this, we need to lift up the experiences and perspectives of Black women, which haven’t been fully included in the anti-racist narrative. In purposefully centering these narratives, we’ll better understand how anti-Black racism intersects with reproductive freedom, violence against Black women, and the devaluing of our family bonds.

She goes on to probe how anti-Black racism is ultimately intersectional and how Black women, especially Black mothers, have played a leading role in resisting it. Here she parallels the fight of Mamie Till with that of the mothers memorializing their daughters in the book. Their losses grow deeper with their ongoing grief and deeper still with the public’s failure to recognize their children’s death (the book dubs this the loss of the loss) and their need for justice. Their experiences and leadership must then be central to our anti-racist movements. As examples of Black women who’ve been fighting anti-Black racism and deserve more prominent recognition, Crenshaw calls to Ida B. Wells’ “attempt to name and disown the horrors of lynching;” Angela Davis’ “revolutionary effort to introduce the analysis of structural racism within the women’s movement;” Johnnie Tillmon’s “fight to center poverty as a women’s issue;” all the way to Sandra Bundy, Mechelle Vinson, Pamela Price, Rosa Parks, and to Audre Lorde’s “prose and poetry on the interconnectedness of Black women’s lives.”

#SayHerName includes a moving foreword by Janelle Monáe. Last year, the Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter, performer, producer, actor, and activist wrote and performed what she called a rallying cry, “Say Her Name (Hell You Talmbout),” featuring several artists and activists like Beyoncé, Alicia Keys, Chloe x Halle, and Jovian Zayne to uplift the names of the victims “so that history won’t repeat itself,” she writes in the foreword. “When you see family hurting like that, you take on a different level of responsibility. It becomes personal. They are family. These are our sisters. We need to take care of each other.” Crenshaw previously told me Monáe’s arrangement was a chant that underscores a ritual of remembrance of Black women.

She classified Monáe’s work as “the embodiment of what we call artivism—the art to activate people.” She sees artivism as an essential piece of the #SayHerName mission because “when you’re trying to write a new narrative and create new ways of knowing, bringing that into existence is a product of art—it’s a product of reimagining the world…so we can see things that we’ve never really spent much time trying to see. Artists have been central to everything we’ve done.”

The #SayHerName movement has been successful in raising awareness for the deaths of Black women at the hands of police. Its namesake book for survivors, activists, and communities will do the same. It exposes the truth and gives a name to girls as young as seven and women as old as ninety-three who were killed by police. It puts an affecting face on those most vulnerable to state violence. It fosters a deeper understanding of the stereotyped and caricatured depictions of Black women and girls. It inspires empathy.

Uncovering such truths has been a considerable part of Crenshaw’s scholarship. As the hashtag campaign has sparked global conversations about how racism and sexism intersect to create a unique and dangerous experience for Black women and girls, the book enriches the discourse. Crenshaw aims to get people thinking equally about all who’ve lost their lives in this way, rather than just a gendered subset of them.

“I hope that it allows people the space and grace to ask themselves, ‘Why didn’t I know this?” she says. “‘I care about racial justice. I care about Black people. I care about all of these things. Why is it that I didn’t know the name of India Kager, or why didn’t I know the name of Michelle Cusseaux?’”

Rita Omokha is an award-winning Nigerian-American writer and journalist based in New York who writes about culture, news, and politics.