Products You May Like

Dolly Alderton is one of this generation’s preeminent oracles for love, romance, and heartbreak. Through both her Sunday Times column, “Dear Dolly,” and her bestselling books, Alderton exposes the inevitable misfortunes of singledom while never neglecting its inherent beauty. Her takes on the ups and downs of womanhood—the messiness of early adulthood; the necessity of dependable friendships; the inevitable heartbreaks, romantic or otherwise—are what we know and love her for. To readers, she’s like an older sister, guiding us through breakups, fights, and first-date mishaps with something like grace.

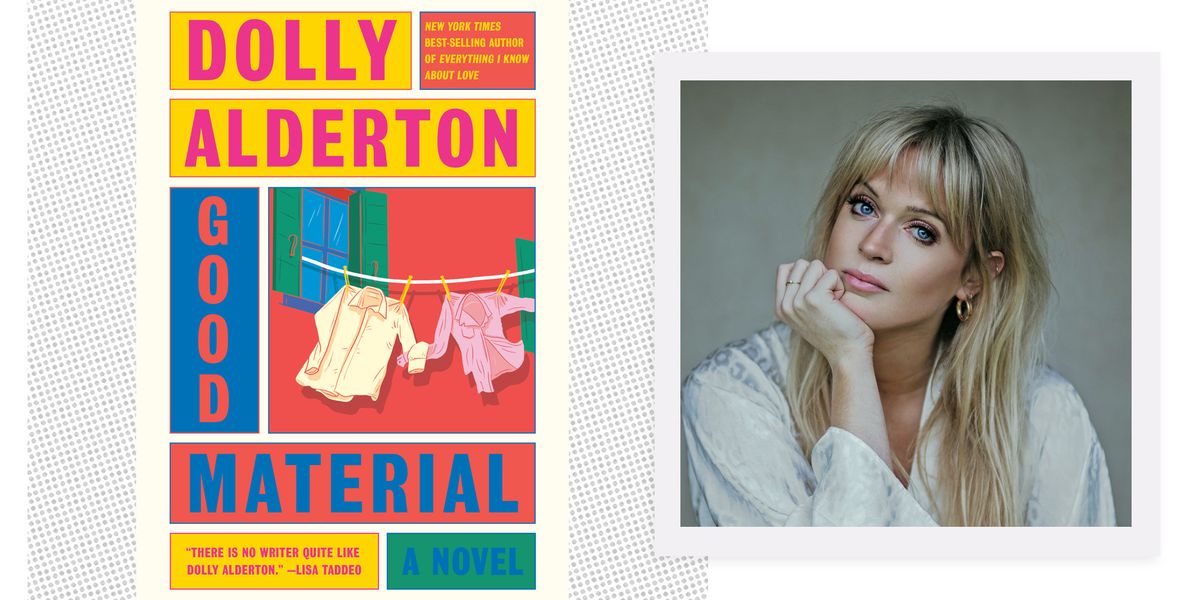

Until recently, Alderton has primarily channeled those themes through the lens of a female protagonist—or, in the case of her autobiography Everything I Know About Love, through her own experiences. But with her latest release, the novel Good Material, Alderton decided to write about a man’s heartbreak from his own point of view. The new novel centers on Andy Dawson, a failing comedian in his thirties trying to navigate life after being dumped by Jen, the seemingly perfect woman he thought he would marry. After vacating the apartment he shared with Jen, Andy moves in briefly with his best friend, Avi, and Avi’s wife, Jane, then finds an unexpected home with 78-year-old Morris, a stoic yet lovable Beatles fan. Through this seemingly dark period of house-hopping, Andy realizes the adult life he thought he’d earned has evaded him—but his new friendships promise an unexpected silver lining.

“When I was a young woman, I found men so confusing. I always have found boys so confusing and exciting and baffling,” Alderton tells ELLE.com. “So I liked the challenge it presented to me as an author. And I liked the challenge it presented me as a woman. It was like an investigation of empathy and trying to understand what happens with heartbreak on the other side.”

Ahead, Alderton discusses the imperfections that define Andy; the particular nuances of male friendships; and what it’s like to have her work compared to Nora Ephron and Nick Hornby.

In the past, you’ve written about the importance of female friendships. With Good Material, was it important you did the same with male friendships?

I’ve written so much about relationships between women and the nature of female friendship. It’s kind of like what I’ve become known for, I suppose, as a writer. While I was making the show [adaptation of Everything I Know About Love] about female friendship, the only books I was reading and documentaries I was watching during that time were about brotherhood. I read and watched a lot about the Beatles, particularly the relationships and the politics among the members. There was a documentary that I got hooked on, which was about Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, the former prime minister and his [Chancellor of the Exchequer]. I also became very interested in the Gallagher Brothers, who made up the members of the band Oasis. I think I was so saturated with the characters, complexities, and nuances of female friendships that I was looking for—just something else to think about and throw myself into. I think it’s no coincidence that after that show wrapped, I decided to write a book about not only male heartbreak but male friendship.

Regarding Andy’s character, I have to say that his sense of humor and self-identity as a comedian shone through. I sometimes marvel at how novelists get comedic timing right through the written word.

It’s so interesting with all the rules of comedy, isn’t it? I mean, it’s a whole industry in and of itself, analyzing what makes things funny. Funny is the thing I most want my work to be. It is hard to laugh out loud at the written word. So I am always looking for little tricks that you can do.

Would you mind sharing some of those tricks?

There was a huge British comedy called Peep Show, and part of its brilliance was that there was a voiceover of the character’s thoughts, and then you would see that in action. I think what you have the privilege of as a narrator, either as a first-person narrator or as a third-person narrator, is being able to access a character’s thoughts and then show how that contradicts their actions or what they’re saying. So I think that is a really neat trick for finding comedy in how we feel or how we’re presenting ourselves to the world. Something else that I learned quite early on, and this is a very simple thing and a very obvious point, is that some words are funnier than others. I think the majority of people, as they’re reading, are reading in their own voice or someone else’s voice. So there are just certain words that, phonetically, are funnier if you say them in your head. So I’m always looking for the funniest-sounding names and the funniest brands. That’s something Nora Ephron said; specificity is what’s funny. So I always try to hone in on the specifics of something in a comedy sequence rather than writing broad descriptions. There are just all these tiny things that you can do to pump up the comedy by another percentage.

Speaking of Nora Ephron, Good Material has been compared to Ephron’s Heartburn and Nick Hornby’s About a Boy. What do you make of these comparisons?

Well, I’m just tickled pink. I mean, what I’m always aiming for is something that is uniquely mine. That’s what all writers and artists are aiming for. But I’m also aware that there should be echoes from all the work you consume if you engage with it properly. So Nick Hornby is one of my favorite writers. Nora Ephron is my patron saint of everything—of life, of writing movies, of love. Every writer, I suppose, has this kind of unique patchwork quilt of other artists who’ve inspired them and whose work they’ve enjoyed, and you just hope that the more that you consume of their work and the more that you make yourself, that somehow there will be an amalgamation. In the words that I write, that’s all I hope for, which is why I just can’t stop rereading. I hope that if I just read and read and read them, they will embed themselves in the DNA of my writing.

At the beginning of the novel, Andy feels isolated from his friends, who now have families and responsibilities. Is this portrayal reflective of how unmarried individuals in their thirties usually feel?

I think something happens when you get into your mid-30s when the differences in life choices up to that point become so much more visible. If you’re the only single one in your 20s or early 30s and lots of your friends are in couples, you feel like you can’t get as much of your friend’s time anymore, or your friend doesn’t want to go on vacation anymore because they’ve got these obligations to a partner. Or every time you see a friend, you look to the left of them, and their partner is there. Those things can be tricky to navigate. Then, when people have babies, you feel the difference in home situations because they can’t go out anymore. The schedule changes, so they can’t stay out late. That feels strange. That’s what Andy’s going through. One of his friends is about to have a third child. From your mid-30s onwards, if people have chosen to have families, they are a family unit. The likelihood is they don’t live in the city anymore because they can’t afford to cram their family into a one-bed apartment, so they move out to a different city or the suburbs. You then go to their home, and it’s a family home. It’s a family home, as you remember it when you were a child. All of a sudden, your friends are the parents who are chopping up vegetables and preparing chicken nuggets. It then starts to feel like a huge change when you are single and childless and your friends have a chaotic family life. It’s like you both are living in different galaxies.

What I found interesting is that Andy finds comfort in his friend’s family unit and home, and he tends to be obsessed with nostalgia and his past. He ruminates on his past relationships, not just with Jen but with his other exes as well. Would you say Andy is in a perpetual state of self-sabotage because he’s obsessed with his past?

I interviewed lots of men when doing research for Andy and his friends. And one male friend I spoke to was talking about his obsession with the past and how the atmosphere that he gives to an experience in retrospect is always better than the atmosphere that existed in the present. I think that there are lots of different reasons why someone could have that sensibility; maybe it’s romanticism, maybe it’s cowardice to live in the here and now, and it’s easier to live in a place that you can’t change. You don’t have to be active in changing the past; in your mind, you can change the details to suit whatever mood you’re in and whatever theory you have about a past relationship or friendship. Nostalgia, I think, is a lovely way to view the world and the past, but I was really interested in how that nostalgia can become a prison for someone moving on in their life and enjoying the here and now. The way Andy’s nostalgia presents itself in a detrimental way is that he just cannot see the reality of his relationship. He’s decided that his past relationship was perfect because he wants to be self-pitying because he misses Jen, and because he’ll never be happy like that again, and he certainly isn’t happy right now. So instead of being able to have a clear, honest, and fair relationship to his own history, he mythologizes it as a way to torture himself.

Speaking of romanticization, Andy seems to do this with Jen. At one point, he states that he feels like Jen is a celebrity of some sort. Does that kind of go hand in hand with the class divide between Jen and Andy and their different perspectives on life?

Yes, that tends to be a British preoccupation. If you call your evening meal this, then you’re this type of person from this type of background, or if you went to this type of school, then you’re this sort of person. We are so preoccupied with class in this country. Class is in discussion with everything, even when it’s not being discussed. It’s so present everywhere. I was thinking about this the other day. There’s like a huge boom in food podcasts in England, with people talking about their favorite meals or what their mom used to make. All I do is listen to celebrities and media figures go on podcasts and talk about food. Why? It’s ultimately because every single one of these conversations is not about food. It’s about class. It always is. It’s always about culture and identity. It then becomes an uncomfortable thing in a relationship because when you live with someone and you’re thinking about building a life with them, you inevitably bring your own home and the way you grew up into your relationship, and that can cause huge clashes. I liked the idea of Jen and Andy exoticizing each other. He’d never met a woman like Jen before. She grew up in London, and he finds that very sophisticated and exciting. I think what Jen finds in him is real authenticity. It was another way of showing what their dynamic was as well as being realistic about the fact that this is a huge part of British culture that we don’t even notice anymore.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Swarna Gowtham is a New York-based writer with a bachelor’s in journalism from Indiana University. In addition to ELLE.com, her writing has appeared in Town & Country Online, Editorialist, Who What Wear, and more. When she’s not writing, Swarna’s rereading her favorite Joan Didion essays and rewatching The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel.