Products You May Like

Seventeen years ago, Laurie Simmons made a three-act Old Hollywood-style puppet musical with Meryl Streep and dancers from Alvin Ailey and the Joffrey School of Ballet. Puppets work in Manhattan office towers and battle over promotions, Streep sings a duet with a ventriloquist dummy, and a large gun tap dances. The Music of Regret was a brilliant assemblage of talent that is being released only now, with its premiere on The Criterion Channel.

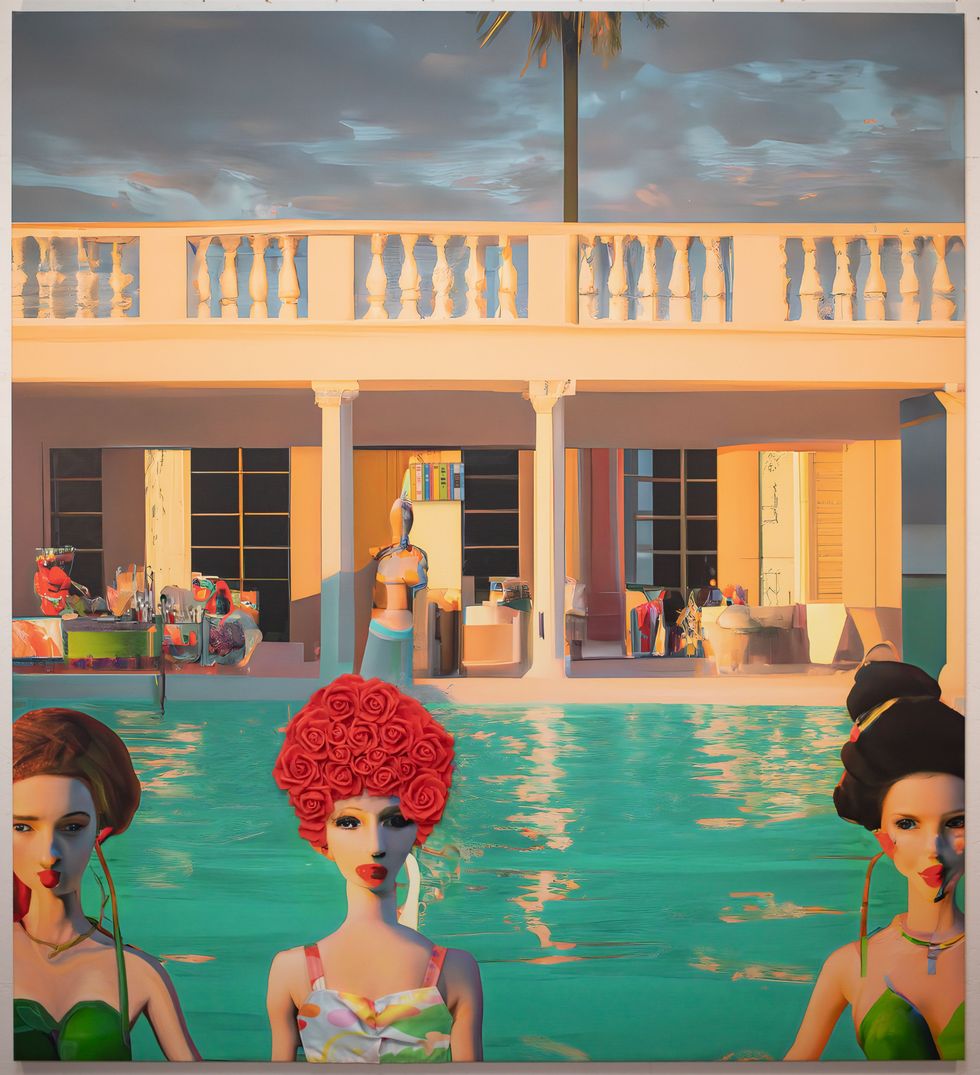

Part of the Pictures Generation, a group of artists that included Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo, and Barbara Kruger, Simmons used dolls, puppets, and dollhouses to stage domestic scenes and examine gender. This month, she has two shows on display. Miami’s Andrew Reed Gallery will be showing Cowboys & Colors Interiors, a selection of images from three of her first photo series in the ’70s and ’80s. Across town, YoungArts is displaying Autofiction, which is Simmons’ latest work and a collaboration with AI.

Few blue-chip artists have been willing to openly engage with AI the way Simmons has. She’s been part of the battles over who can take credit for the creation of an image since she began her career. “What’s kind of scary to me is when I see comments on Instagram that think that people using AI are the devil because it’s art theft,” she says. “Issues of authorship have been around my work since the first photo I took, which was a sink made by a toy company called Shackman in downtown New York placed in front of a piece of wallpaper that was drawn by a wallpaper designer in the 1940s. I authored none of that. I set it up in a very done way, I made the decision to shoot this sort of very blank photo and then I was off to the races. It doesn’t feel that different to me.”

Simmons spoke to ELLE.com about whether the passage of time reframes her work, the potential she sees in AI, and why Americans are looking to dolls right now.

How does it feel to have the film coming out 17 years later?

I’ve been thinking about that. I know a lot of filmmakers and my daughter makes movies and TV shows and I think in that world the expectation is to get feedback and awards and get everybody’s attention immediately. But as a visual artist I think we understand that our job is to be futurists and seers and it’s both defensive and natural to think that people will revisit our work later.

So, first, let me say that having a film on the Criterion Channel is 100 percent a dream come true and that’s not something I say very often. But the idea that it was made so long ago and is now getting that sort of attention, as an artist, is not surprising to me. I think if I were just a filmmaker maybe it would be super frustrating and I’d be focused on everything I didn’t get at the time, but it’s happened to me so much along the way in terms of my work and my career.

Is the context of the film a little bit different, given the time that’s passed?

The Music of Regret was very personal snapshot in time for me because I wanted to start over. I wanted to start fresh in my work. There was a thought like I have to strip my work of everything. So before I did that, I made a movie where I took all the characters from my work and brought them out and made a musical and basically said goodbye to them. The subject of regret has been in my work from day one and is still there in a really big way.

How did Meryl Streep get involved?

We had a very long friendship. Her husband is a sculptor and we were in the same crowd. We were at her wedding. I’ve known her through the years. When I thought about who I wanted for the movie, I thought about asking Meryl but friendship doesn’t mean someone will say yes. I’m friends with so many people but if I thought their projects were goofy or dopey and they wanted me involved I would say no. So I was very nervous and apprehensive about asking her but I also knew that she had a beautiful singing voice and that she would also have a chance to sing with co-star Adam Guettel, Richard Rodgers’ grandson and the writer of Light in the Piazza. I found out we’d both seen it like five times, we both fell in love with that musical. She said yes. Cinematographer Ed Lachman shot it. It was almost like, dream as big as you possibly can about a three-act puppet musical, which I did.

It must have been a wild experience.

It was, because I’d never directed before. My daughter, Lena Dunham, hadn’t made Tiny Furniture yet. In fact, my daughter came to set and she claims that’s where she was bitten by the movie bug. Both our kids were on set. I vividly remember the first day. It wasn’t a small crew and I just had zero idea what to do when you walk onto a set as a director. It felt the most like jumping into a freezing cold swimming pool and I just thought I’m going to do this and I can do it.

Has the exposure to your daughter and having conversations around the dinner table given you an education in directing?

It’s not the dinner table, because we don’t talk about [work]. It’s being on set and watching her interactions with people. My observation on Lena’s sets was that people love her, working with her. I couldn’t imagine any other way.

I asked a version of this question before but I’m thinking about it with Cowboys & Color Interiors. With gender being at the core, is your work something people see in a different way now?

Absolutely, 100 percent. I mean, some of that work I made in the late ‘70s. The kind of gender roles that I was exposed to, the kind of rigidity, the things that I was railing against, the things that turned me into a young activist, the world is a very different place now. But obviously we’re still facing a lot of the same issues. I think that with the very strict definitions of gender—things have loosened up. Simple little things like putting a boy in a pink snowsuit would not be frowned upon right now. Just the most basic sort of boring little details. But I think that in terms of an extended exploration of gender in my work, the world has proven to be very fertile ground for me.

The things that I’ve experienced like living through the AIDS pandemic, having a trans child, meeting all of his friends, it’s just been incredible how inspiring it’s been in terms of my work and in terms of providing visual and philosophical and psychological and political material. I feel frustrated with the world at large but also grateful for its evolution and its ever supplying me with subject matter.

What has working with AI been like?

Somehow, I’ve ended up in a lot of conversations and things in the press, [but] I am not an AI artist now. I didn’t expect to be using it. I was introduced to it about a year and a half ago and it just got to me right away and it feels to me like another tool in my artist toolbox. Will I be using it a year from now, two years from now? I can’t say. I’m considered a lens-based artist but I’ve made sculpture, I’ve made movies. I put down my camera a few years ago for various reasons and AI has given me a way to work where I also do not have to look through a camera.

The most interesting thing about AI is the controversy, fear, conversation, sensation, apocalyptic thoughts that are surrounding it. There’s a kind of hysteria surrounding it and I, again, I’m using it as a tool. I try to keep myself as well informed as possible. I’ve gone down a rabbit hole of podcasts and reading and what do the greatest minds of our time think about it and I can tell you people’s thoughts about it, really people’s thoughts about it are as diverse as snowflakes, the color of the rainbow, whatever cliché you want to use. Nobody is in agreement about it.

Do you enjoy it? Is it a fun process?

I love it. I remember reading something about Stephen Sondheim writing lyrics. He would lie down with a yellow pad and pencil and write lying down on his sofa, relaxing. I thought that’s actually the best way to work. I just love that and there’s a way that at night I can just lie in bed with my laptop and start to see images appear. I’m not in the studio with models or dolls or my camera.

The most interesting thing for me is that no one—I think the surprise with a lot of people about my newest pictures is how seamless it feels in terms of the rest of my work. I think it’s important to point out that I don’t use my name in the prompts. The prompts never say, in the style of Laurie Simmons.

Oh, that’s interesting.

I think people assume. That’s why I’m glad I’m getting to tell you that. I think people assume that I say, “a girl in Times Square on New Year’s Eve watching the fireworks in a designer dress” and people assume that I then say “in the style of Laurie Simmons,” but I don’t. I have other prompts that I use to get where I want to go but that’s one that I do not use.

Forgive me for my ignorance, because I’ve never used AI, but how detailed are your prompts?

I need to give a time and a place and a feeling. I’m as surprised as you that things came out that look like my work. I might throw in a word like “doll” or “doll-like.” It’s like the thousand monkeys with typewriters thing. How many people would we have to put in a room to get things that look like that or how many of us would have things that look the same?

The editing process has been huge for me. Shooting 1,000 pictures and finding the one picture because I placed a doll that I bought, an old doll, in the center of another dollhouse that I bought and shoot 1,000 pictures and it’s the one picture where the light and the angle and everything are [right.] That’s not at all different in AI. There’s a huge number of misses to get one that feels like a hit to me.

I know you’ve been asked this a million times, but what do you think of the idea that, with Barbie, dolls are really captivating people right now?

I know what captivated me in the beginning. It’s interesting. Enough time has passed so that most people’s lives have touched on Barbie at one moment or another. So, in a sense the familiarity with that particular doll was going to make that be a feel-good movie. But I think that the way that Greta [Gerwig] addressed gender and gender roles head-on was also the right time for that, even though I feel like for me it was an investigation that started 40 years ago. I think right now people are really ready to address that and have a feel-good movie about it. It’s more interesting to watch the Barbie movie than to really address what’s going on with Roe v. Wade, isn’t it? The last scene of the movie was going to the gynecologist. It’s quite crazy. So much is at stake right now, so much is in peril from books to women’s reproductive rights. Did you ever thing you’d live in a country where books were banned?

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Adrienne Gaffney is a features editor at ELLE and previously worked at WSJ Magazine and Vanity Fair.