Products You May Like

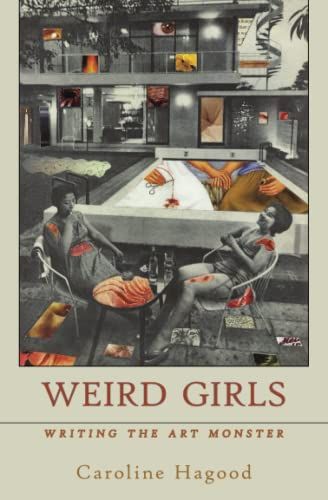

How to even chronicle the exhausting and hilarious arc of the days that started at 5 a.m. when my kids banged on the drums we gave them for some reason (why?!), and culminated in my attempt to write my essay collection, Weird Girls: Writing the Art Monster. Weird Girls considers the plight of women writers (and particularly mothers) to make not only cakes and babies but also art, and the very conundrum I was facing myself: how to carve out space to be creative, how to push back against the endless stream of domestic duties to get the writing done, and all without being an actual monster to everyone I encountered? It was not easy.

The art monster is an ancient idea, but one given an official name by Jenny Offill in her 2016 novel, Dept. of Speculation. In her book Offill’s protagonist (referred to only as “the wife”) planned on being an “art monster” writer, someone who gets to be passionately dedicated to his or her (but usually his) creative practice (because his wife watches the children while he does so). But then she got married, had a kid, and found herself drowning in domesticity, which poses a great challenge to artmaking. And, like Offill’s protagonist—despite the kids beating on drums in the background and my efforts to be a (hopefully pretty good) mom to them—I was on a quest to simultaneously write about and be this very particular kind of creative monster: someone ferociously, almost ferally, dedicated to the writing. But could these two roles ever really coexist?

Some women writers have pushed back against the term, understandably interpreting the “monster” in “art monster” as an allowance of acting like a jerk in the name of art. For me, however, the concept refers more to how society has historically made monsters who dared to live out their mad fantasy of venturing out of the home to make something of their own, dating back no doubt to the first woman who started a fire with her own two hands. In my view, the “monster” in “art monster” doesn’t refer to acting like an actual monster and abandoning your kids to write, but it does serve as a symbol of wild invention that can help you, say, get up the gumption to inform your husband that, yes, he really does need to take the kids to the playground so you can finish your effing book.

But then I came upon an unexpected twist in my journey of attempting to write my book while parenting: Though my kids hindered that artistic process in a thousand million ways, they also, counterintuitively, fed it to an extent. Or, let’s be honest, at least that’s how I had to see it to survive. Which is all to say that, in addition to reminding me of some of the poignant art monster qualities that got adulted out of me (endless wonder and innovation, imagination as a way of life, not caring what people thought, not distinguishing magic from reality, for instance), my son also became my partner in literary crime.

During the time I struggled to write Weird Girls, my kids came to see me read for the first time. I have a picture of the moment these two theoretically irreconcilable worlds touched. There I was: reading about stalking my own creativity through tundras of domesticity; and there were my kids: the central inhabitant of these tundras, sitting crisscross-applesauce in the front row. It seemed to blow their little minds that I existed as something other than a humanoid teat, but this discovery of who I was in my entirety turned out to be important for all of us. After the reading, my son had many questions. Was I a famous writer, for instance? Um…no, not at all. And, from that night on, after any intense experience, he’d ask me whether I was going to write about it. Um…absolutely.

And then there was the big question. One night as I was putting them to bed, my son asked about the meaning of life, like why do we do it? Even my youngest could see something crucial was afoot. She decamped from her trundle bed to poke her head into the moment, shoving her face so close our eyes we were almost touching. But before I could answer the question, she lost interest and tried to eat my necklace, saying, “Mommy, back ride.” This was my cue to flip onto my stomach so she could board my back like a sea vessel. I did so. And my son performed his part of the act: holding my hand way too tightly.

It hurt to have him squeezing my hand and her on my back, but there was also some meaning of life to be found in their nightly demonstrations of outlandish tenderness. I pictured my daughter ferreting me off on a “back ride” whenever I wanted to run away. I’d start a nice life by the sea, somewhere far from date nights and PTA meetings, where I could write in peace or even just go to the bathroom without small people busting in to touch me with ketchup fingers while singing Frozen. The whole bizarre premise of our bedtime routine was probably the meaning of life my son was asking about, or one of them. But writing was also part of it for me. How to articulate this to my son? I finally said, “I think the point of life is what you love, like I love both of you and I also love my writing.” There was silence and then he said, “Oh, like how I love you but also chess and my stories?” Absolutely.

These tender moments make me stick around even in the darkest hours of the maternal odyssey. But still I longed for more. Was that so wrong? Sometimes I feared it was. Like someone/something out there could sense it and would smite me for wanting to be larger than I was. My house was haunted by the complexity of life that motherhood couldn’t, despite the propaganda, sterilize or Febreze away. After cuddling with them that night, as I passed the full-length mirror, I glimpsed something monstrous that turned out to be just me without my glasses. Yet I felt I’d seen my own potential wildness beckoning to me from the shores of creative lands I couldn’t reach with two children on my back. Or could I? But how? As Virginia Woolf’s “a room of one’s own” simply wasn’t possible for me, the only solution I found was to include my kids in my creative life. Even if that meant attempting to type with both on my lap smearing my keys with what I could only hope was chocolate.

After my son came to see me read from Weird Girls, he started discussing the book-in-progress with me. Once he grasped the concept of the art monster, he liked to identify characters in his books, TV shows, and video games as such. Hermione!, he shouted to me last week from the pages of his first Harry Potter. As I was writing, he’d place his little notebook across from mine so we could write together like some old-timey screenwriting duo: me on Weird Girls and he on his (admittedly shorter but no less serious, let me tell you) “stories” for school. He wrote one called, “SNAKES!” that had both a table of contents and a glossary. He’d ask me what “my story” was about and I’d do the same until our narratives started speaking to each other from across the table. Most of all, he likes to help me with edits. I run things by him. In fact, he weighed in on the other potential title for this piece, swiftly nixing it with an opinionated “nuh-uh” because it “had too many words and no Mr. Potato Head.” And who in their right mind would want to read anything without Mr. Potato Head?

Caroline Hagood is an Assistant Professor of Literature, Writing and Publishing and Director of Undergraduate Writing at St Francis College in Brooklyn. She has published two books of poetry, Lunatic Speaks and Making Maxine’s Baby, one book-length essay, Ways of Looking at a Woman, and one novel, Ghosts of America. Her writing has appeared in The Kenyon Review, the Huffington Post, the Guardian, Salon, and the Economist, among others.