Products You May Like

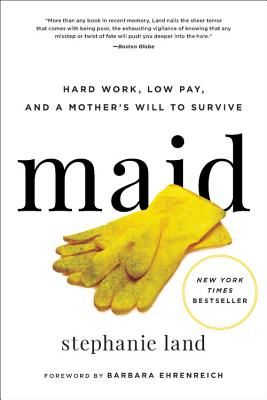

The first line of Maid, Stephanie Land’s remarkable 2019 memoir about working as a maid during her impoverished early years as a single mother, reads: “My daughter learned to walk in a homeless shelter.”

In Netflix’s series adaptation of the book, which is now streaming, that scene never takes place. In fact, Alex—the show’s main character, a fictional stand-in for Land played by Margaret Qualley—never stays at a conventional homeless shelter at all. This is just the first in a series of differences between the source material and the show. Yet, the picture that emerges out of these modifications is just as tender and lonely and outrageous as Land’s real-life story, which exposes the severity of the poverty crisis in the U.S.

Perhaps the most significant change is that the series fully fictionalizes Land’s experience. In addition to renaming “Alex,” Land’s abusive ex—called Jamie in the book—becomes Sean, and her daughter Mia turns into Alex’s daughter Maddy. Land’s parents, who are unnamed and barely appear in the memoir, are rechristened as Hank and Paula and given expanded roles in Netflix’s retelling.

Paradoxically, most of these tweaks were made with the intent of staying as faithful as possible to the spirit of the book, according to showrunner Molly Smith Metzler. “When I started thinking about how to adapt, I clung to the effect the memoir had on me,” she tells ELLE.com. “The memoir is riveting to read, but it is an extremely lonely experience for Stephanie Land. She doesn’t talk to anybody. I wanted to capture how isolating her experience is, but it’s not amazing TV for a character to not interact with anybody, so our first challenge was to populate the world and also to make sure she felt very alone.”

In this respect, the show succeeds. Maid is an intensely lonely experience—not just for Qualley’s Alex but for the viewer as well. We follow Alex as she claws through the labyrinthine system of state-run benefits, trying to cobble together enough work to qualify for a childcare subsidy that will allow her to put her daughter in daycare so that she can work some more. We watch Alex’s cash reserves shrink from $20 to $18.10 to $15.50 to $9.20 to $2.13 on screen as she rings up groceries, all of her mental math playing out onscreen. We’re there with her when her wealthy client, Regina (Anika Noni Rose), sneers at Alex like she’s less than human; when Sean (Nick Robinson) throws a glass pitcher at her head; when her mother, Paula (Andie MacDowell, Qualley’s real-life mom), rages that Alex is no daughter of hers. When Alex is filling out paperwork for her court battle over custody of her own child, we witness reams of numbered pages giving way to worksheets whose titles openly taunt her: You are an unfit mother. You will lose this case.

Metzler’s hope is that putting all those cracks in the fourth wall will allow the show’s message about the injustices of poverty to better reach viewers. “I really wanted more people to know this story. … The memoir made me furious that we fail her as a country.”

Maid already seems to have made a significant impact on the cast. “I learned a lot about the institutional failures of the social safety nets in this country and the welfare programs that are in place,” says Nick Robinson. “You can’t be working X amount of hours and also get subsidized childcare, but it’s like, If I don’t have subsidized childcare, how can I work?” Anika Noni Rose believes the show’s ability to inspire empathy for people in Alex’s situation is a huge part of what makes the story worth telling. “The point is that poverty is a space that is so difficult for people to get out of. Working hard is not enough. Getting assistance from the government is very often not enough. Our food stamp program is nutritionally deficient and unable to feed a family—you’re talking about a dollar per person per day for the week. People who’ve worked their entire lives are not getting a prescription because they need some food.”

Still, for everything that Alex endures, as I watched I couldn’t help wondering how much harder her experience would be if she weren’t white, straight, young, and pretty. For Andie MacDowell, that’s the point: “I thought it was really interesting to see that [Alex’s experience] could happen to anyone. Here you’ve got someone who’s brilliant and articulate and capable, and she has to navigate that system.” Rose agrees. “Poverty happens to people who in this country are groomed to be at the top of the game. It happens to people who are told that they can be and should be at the top. Most people are about a paycheck and a half away from not having rent, and that’s a really frightening space to be in.”

Even so, it’s important to note that Alex’s isn’t the typical face of domestic violence or extreme poverty. According to an info sheet from the Office for Victims of Crime, Black, Native, and multiracial women experience higher rates of domestic violence by a significant margin, and queer women are significantly more likely than straight women to experience rape, stalking, or physical violence by a partner. Data gathered from the U.S. Census Bureau also shows that the poverty rate for Black and Hispanic Americans is more than double than that of white Americans. Metzler tried to keep Alex’s privilege in mind while adapting the story. “In episode 8, Alex hits rock bottom. One of the things I tried to think about is that, for most people, the story ends there. It’s this incredible resilience she has that gives us episode 9 and 10. Alex gets up by a hair, and that’s what makes her an outstanding exception to this rule, but most people don’t get out of episode 8.” One might imagine that Alex’s whiteness and likable appearance have something to do with that.

Most of the major events in the memoir survive the jump to TV, just somewhat rearranged: a pivotal car crash from the middle of the book takes place in the first episode of the show; a housing arrangement in which Alex barters yard work and cleaning services for rent goes sour in a matter of days instead of slowly breaking down over a year or so. Ultimately, none of these smaller alterations actually change the story very much, but the show does make a few major departures from the book in three key areas: Alex’s family situation, her love life, and her relationship with her maid clients.

Alex’s Parents

Land’s family of origin takes up very little space in the pages of her memoir. When she first leaves her abusive partner, Land’s dad lets her and her daughter stay with him for a few months—but that show of hospitality ends abruptly when Land learns that he’s been violent with her stepmother. On a separate occasion, Land’s mother and her much-younger husband insist that she join them for burgers, then sneer at her when she’s unable to pay the bill. Outside of these brief appearances, Land’s parents don’t show up at all.

Not so in the series: Alex’s journey is as much about her love for her daughter as it is about her efforts to care for her own mother, an eccentric, mentally ill artist named Paula. Though it seems serendipitous, the decision to cast MacDowell was not a foregone conclusion. “I think everyone was like, should we cast her real-life mom? But nobody wanted to bring that up,” says Metzler. Ultimately, it was Margaret’s idea. “She wanted her mom there, and it changed the whole electricity of set, because they both wanted each other to do their best work.”

Most of the time, MacDowell’s Paula is a delight to watch. She’s outrageous in both behavior and appearance, and boy, does MacDowell commit to the role. “It was so much fun to play her: push the boobs up, more boobs, more skin, more inappropriate,” she says. “She’s broken, but at the same time, she’s the life of the party.” Paula is at times a hard character to love, especially when you see her fail Alex again and again, but some of the most affecting moments of the series take place while Alex is picking up the pieces. It’s here that Qualley and MacDowell’s IRL mother-daughter relationship makes the biggest impact as well. “Margaret’s always been really empathetic in wanting to know more about me and about my relationship with my mother,” MacDowell says. “I think because it helps her understand herself and her journey.” And for her part, MacDowell is well aware of her role in the story. “The reason I’m there is so you understand Alex’s trip. I was very conscious of that: the better job I did, the more I helped Alex.”

Knowing that Land can’t rely on her parents to help her is a big part of what makes reading Maid the book such an isolating experience. Rather than disrupting that sense of loneliness, elevating Paula to a major role in the series makes Alex’s isolation feel even more vivid. Paula can barely be trusted to take care of herself, let alone help Alex in a meaningful way. More than once, Alex’s decision to let Paula babysit her daughter proves to be a mistake. As we learn more about Paula’s history as a repeated victim of domestic violence, we gain a painful understanding of Paula—and how Alex got caught in her own cycle of abuse. This added context only further highlights the fact that, even with her mom nearby, Alex is more alone than ever.

Alex’s Love Life

The series shows us far more of Alex’s relationship with her daughter’s father than we ever see in the book. On the page, Land’s ex-husband—whom we know as Jamie—mostly shows up to take their daughter on weekends while Land is cleaning houses. There are plenty of passing references to darker chapters in their relationship (instances of physical abuse, an acrimonious custody battle), but for the most part, these events remain in the background of Land’s story. In the show, Maddy’s father Sean has a much larger role. The first episode begins with Alex scooping up Maddy and leaving Sean in the middle of the night, and the back-and-forth of their contentious relationship remains a major storyline throughout the series.

Key to that storyline is Sean’s struggle with alcoholism. From episode to episode, viewers are brought on “this roller coaster ride with Alex where it seems like Sean is getting better, and then he’s not, and then he is, and then he’s not, and then he is, and then he’s not,” says Robinson. Like Alex, Sean is a product of his environment: “He’s in large part traumatized from his upbringing. He came from an abusive household, he was modeling the behavior that he had been taught, and I think he felt just trapped by his own circumstances. He just had a lot of anger and resentment towards the way his life had turned out. It does not excuse his actions, but I can understand why he was angry.”

So could I. In fact, one of the most disturbing aspects of the show is the way that Sean subtly, gradually charms the audience—just like he first charmed Alex. That’s on purpose, says Robinson. “He has to be really bad at the beginning, [because] you have to understand why Alex left, but then you have to see what it was about their relationship that drew her in to begin with.” It’s easy to root for Sean to get better, not just for Alex and Maddy’s sake but for his own, which makes it all the more upsetting to watch him repeatedly fall back into old, abusive patterns.

Alex’s love life isn’t confined to her abusive relationship with Sean, though. Several episodes in, we’re treated to a Tinder date gone awry and an old coworker named Nate (excellently played by Raymond Ablack) surfaces as a knight in shining armor who’s always had a thing for Alex. Even though she’s clearly attracted to him, Alex tells Nate she’s not in a place to date. That’s fine by Nate, who insists that the support he’s offering her is unconditional. But later on we learn his kindness does have strings attached, after all—reiterating the series’ message that no one is going to save Alex except maybe, if she’s really lucky, herself.

Alex’s Clients

In the book, Land’s work as a maid spans several different cleaning services and scores of clients. We learn a lot about the houses she cleans and the people who live in them, some of whom appear in the show just as they did in the memoir: the Porn House, for example, where a husband and wife sleep in separate bedrooms (his has a stash of dirty magazines, hers a stack of romance novels); the Loving House, where a retired old man cares for his ailing spouse. But Land never dwells too long on any of her clients in particular.

That’s where the series differs. Alex’s first-ever client stays with her throughout the series and even goes on a journey of her own. Swathed in thousand-dollar cardigans and adorned with jewels, Rose’s Regina is a high-flying attorney who initially turns up her nose at Alex. It takes a few episodes before Regina begins to see Alex as a person, not a servant—and before Alex realizes that Regina’s wealth can’t erase her deep sense of unhappiness—but by the end of the series, Regina proves to be not just a valuable ally to Alex, but also a dear friend.

It’s this arc that’s a little hard to stomach, and not just because it’s a little too convenient and kumbaya to fully square with the otherwise-dismal world in which Maid takes place. Something feels almost gotcha-like about watching a poor white maid struggle to touch the heart of her imperious Black employer, as if well-paid TV writers are patting themselves on the back for “winning” a wokeness contest in which the viewers didn’t even know they were competing.

But the decision to pit Alex against a rich woman of color starts to make more sense upon hearing Rose liken it to a game she used to play in theatre school. “[It was] called One and Two, and if you were a number One, you acted a certain way, and if you were a number Two, you acted a certain way, and that number would change as you walked around the room and came in contact with certain people. And that’s a real thing, you know? As a Black person with all the trappings of the good life, you walk out of your house, and you’re a number One, until you run into the police officer who make you a number Two. If you are a poor white person in a space where you feel like nothing, our system has taught you that when you run into a person of color, you are immediately a number One.”

In other words, Regina and Alex are caught in a game of One and Two: “Were Regina not draped in cashmere and diamonds—and even sometimes when she is—she would be seen the same way that she is seeing Alex, in spite of all that she has worked for and the privilege that she has attained.” In that light, the juxtaposition of Alex with Regina feels a lot more purposeful: Their relationship is supposed to tell a story about relational power dynamics—and the difficult work of undoing them.

Even so, Regina’s characterization feels a little on the nose. (While having a breakdown in one scene, she shrieks, “A week ago, I was eating arugula in my corner office!”) The fact that I am able to say “a little” is a testament to Rose’s rich, layered performance. In her hands, Regina becomes a real person, prickly and guilt-ridden and capable of change. And change she does. Her growth as a character resembles an exaggerated version of the emotional journey on which Maid hopes to take its viewers: one in which the vast, fuzzy-for-many concept of extreme poverty is given a face we just might be able to recognize.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io